Why Did Mid-Budget Films Disappear? How DVD Sales Created Cinema's Safety Net

In this series: The Importance of Physical Media

Why did mid-budget films disappear? Why don't studios make the kind of £30-50 million adult dramas, thrillers, and comedies that defined cinema from the 1980s through the early 2000s?

The answer lies in home video economics and what happened when streaming replaced it.

Streaming is better than physical media in almost every way that matters to audiences. Instant access, no rewinding, no late fees, no driving to the shop. You can start a film on your phone and finish it on your telly. It's brilliant.

But something broke when we made the switch. Something most people haven't noticed because it's not about watching films, it's about making them.

The film industry lost its safety net.

For decades, home video meant a film could bomb at the box office and still make its money back. Studios knew this when they greenlit projects. It changed the entire risk calculation. A £40 million drama that underperformed theatrically? Fine. It'll probably recoup through rentals and sales over the next year or so. The theatrical run gets people talking, but home video is where you actually make the money back.

Streaming doesn't work like that. I'm not saying it's worse for viewers (it isn't). I'm saying the economics are completely different. A film that builds its audience slowly over five years, used to generate revenue from each new fan who discovered it. Now? That delayed discovery is worth nothing unless it happens fast enough and large enough to shift subscription numbers.

Which it usually doesn't.

How Home Video Revenue Changed Film Economics

There's this clip from Matt Damon on Hot Ones in 2021:

You know, we made more money on those DVD sales than in the entire box office. And it changed everything about the business.

He's talking about how backend revenue from home video changed what studios were willing to risk. You could make a film that didn't make sense as a pure theatrical play because you had this safety net underneath it. Worst case scenario, it finds its audience slowly through rentals.

Time was an asset. A film that confused people on opening weekend could be rewatched, re-evaluated, passed around. Some films just need time.

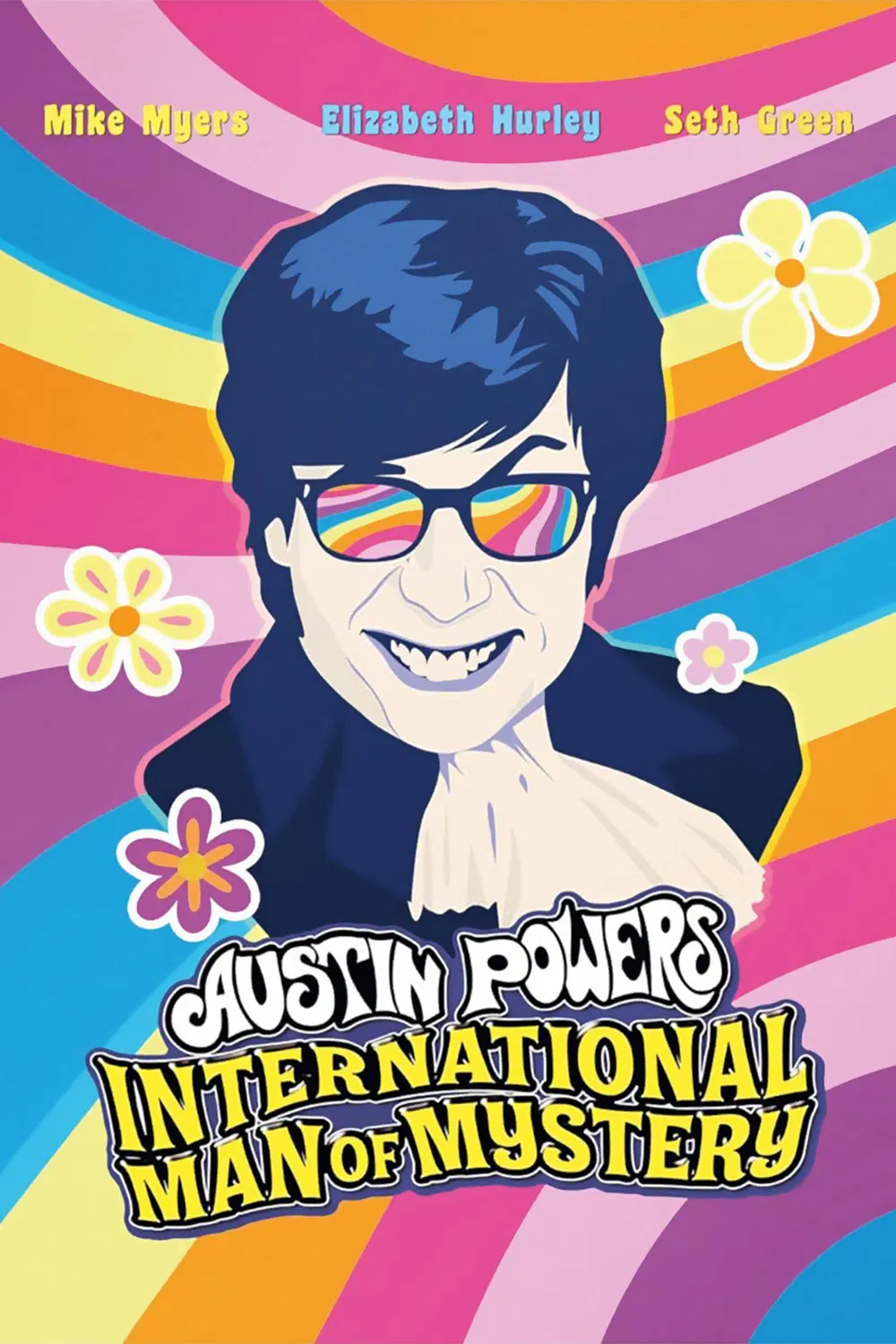

Austin Powers Shouldn't Have Become a Franchise

Austin Powers: International Man of Mystery made £53.7 million domestically, £67.7 million worldwide in 1997. Decent numbers for a comedy. Not great. Not "let's immediately greenlight two sequels" money.

But home video changed everything. The film was endlessly quotable and got better on repeat viewings. VHS and DVD sales turned it into this cultural phenomenon. By the time The Spy Who Shagged Me came out, it opened to £54.9 million in its first weekend. That's nearly what the entire first film made domestically. In three days.

The third film did over £296 million worldwide. Without home video building that audience, Austin Powers is a forgotten cult comedy from the late nineties. The safety net didn't just help it break even - it turned delayed success into something massive.

The Thing Failed Twice (and Succeeded Once)

John Carpenter's The Thing is considered one of the greatest horror films ever made. In 1982 it was a commercial and critical disaster. £19.6 million domestic against a £15 million budget. Once you account for marketing and distribution, Universal lost serious money.

The timing couldn't have been worse. Released two weeks after E.T., when everyone wanted friendly aliens. Roger Ebert called it "a great barf-bag movie." Most critics savaged it. Should have been the end.

VHS saved it. Horror fans passed tapes around. The film got re-evaluated away from the summer of Spielberg. By the late eighties it was a cult classic. Now it's in film schools, on every horror list, constantly referenced.

You must remember the time when it was released was the summer of E.T. And it was a very bleak and hopeless film...

— John Carpenter, interview (1996)

The rental market gave it time to find people who got it.

Why Transactions Beat Subscriptions (For This)

Here's the key thing about how video shops made money. Whether you rented Terminator 2 or some obscure foreign film, the shop got paid £3-5 either way. Same transaction.

No pressure to push you towards whatever was statistically most likely to keep you browsing longer. The shop just needed you to find something and pay for it.

This meant films could sit on shelves without justifying themselves constantly. A niche title that got rented once a month was fine. Not great, but fine. Over time those occasional rentals added up. The shop was patient. Studios were patient. Slow burns were just part of how it worked.

Physical media also created these recurring windows where you could make money off the same film multiple times. Something bombs on VHS in 1998. Then it finds an audience on DVD in 2003. Becomes a collector's item on Blu-ray in 2015. Each format change is another chance to sell it again.

Studios kept massive back catalogues because once manufacturing is set up, keeping things available costs relatively little. 500 copies a year doesn't sound like much. But over twenty years that's 10,000 sales at £15 each. £150,000 from a film you wrote off as a failure back in 1995.

The long tail actually generated income. Patient discovery was worth something.

The Trade We Made (And Whether It Was Worth It)

I need to be honest. Physical media was expensive and inconvenient for a lot of people.

Building a collection meant spending £15-25 per DVD. Hundreds of pounds for even a modest library. You needed space to store it. Video shop rentals were cheaper at £3-5 per film, but you needed transport, you had to remember return dates, you paid late fees when you forgot. And if you lived anywhere rural, your options were probably limited to whatever Blockbuster stocked.

Which meant fifty copies of Titanic and maybe one from Bergman if you were lucky.

Streaming solved real problems. £10 a month, thousands of films, no storage, no transport needed. Someone in rural Scotland with mobility issues now has access to more cinema than the best video shop in London ever stocked. That's accessibility in a way physical media never achieved.

So I'm not saying streaming is bad for audiences. It isn't. The question is whether we can have both things. Accessibility and economic sustainability for certain types of films.

Right now we've traded one for the other. Physical media gave filmmakers a safety net but limited audience access. Streaming gives audiences access but removes the safety net. The result is that increased access for viewers means decreased viability for mid-budget cinema.

Nobody planned this. It just sort of happened.

Why Streaming Revenue Doesn't Reward Delayed Success

Licensing deals for streaming typically involve flat fees or revenue-sharing that doesn't scale with how long a film takes to find its audience. A film that builds viewership slowly over five years generates the same revenue as one that gets the same total views in its first month.

Time doesn't compound anymore. It just passes.

The British Film Institute's economic review found that "the model of independent production is being shaken at its foundations" because revenues aren't keeping pace with costs, even as digital channels grow.

Most platforms don't even tell filmmakers how many people watched their film. You might know it's on Netflix but you've got no way to know if anyone's actually watching it. The opacity makes it impossible to understand what's working.

The revenue-sharing model in streaming can be less predictable and potentially less lucrative for content creators.

— Motion Picture Institute

Some films find homes on niche services. MUBI, Criterion Channel, Shudder. These work more like the old model at a smaller scale. But they're exceptions serving small audiences, not the mainstream that determines what gets greenlit.

Without guaranteed backend revenue, studios have retreated to extremes. Massive franchise blockbusters (guaranteed box office) or micro-budget indies (negligible risk). The middle has hollowed out.

Even when a film finds an audience over time on streaming, that attention rarely converts to meaningful revenue unless it happens quickly and at scale. And most films don't happen to go viral.

What Happens When Discovery Arrives Late

When a platform decides a film isn't worth hosting anymore, it doesn't just stop earning. It vanishes.

Physical media had redundancy built in. A film that performed poorly could circulate through used shops, library sales, collector exchanges for decades. Discovery could happen any time, and each discovery meant a potential transaction.

Streaming centralises everything. When a film leaves a platform, it's gone from search results, from algorithms, from browsing. Interest that develops years later arrives too late to matter.

This is particularly cruel because the films that benefit most from time are exactly the ones streaming punishes. Unconventional works, films ahead of their era, things that initially confused audiences. These needed slow circulation. Streaming's metrics don't allow for delayed appreciation.

What This Actually Means

The safety net hasn't vanished completely. Boutique labels like Criterion, Arrow, Eureka keep proving the old logic works at a smaller scale. Delayed discovery can generate revenue when people can buy films outright.

But these are niche operations. They can't preserve the economic model for an entire industry.

For most films, once theatrical and streaming windows close, there's no plan. No mechanism to monetise delayed discovery. Just a calculation about whether immediate engagement justifies this quarter's costs. As explored in Why Streaming Platforms Are Creating a Film Preservation Crisis, when platforms decide a film isn't worth keeping, it doesn't just stop earning - it can disappear entirely.

We replaced a system that tolerated failure and rewarded patience with one that demands immediate success. That's not necessarily wrong. Just different. But we should be clear about what got lost.

The video shop era wasn't perfect. Access was limited, costs were real, distribution was unequal. But the economics created space for films to exist on margins, to find audiences slowly, to matter to small groups without algorithmic validation.

That space is closing.

Whether what replaces it will be better depends on whether we value convenience over resilience, instant access over economic sustainability. There's an experiment happening. Can an industry built on creative risk survive without the safety net that made those risks bearable?

Early results suggest maybe not. At least not for the middle. The very large and very small seem fine. Everything between is learning to be afraid.

Film images and logos used in this article were sourced from TMDb (themoviedb.org).Explore more on these topics

Christopher Bray

Engineering open algorithms to map the invisible connections of cinema. I build discovery tools that look beyond streaming catalogs to ensure film history isn't lost to the algorithm.