The Importance of Physical Media: Cinema’s Safety Net

In the transition from the video store to the streaming queue, we were promised convenience. We gained instant access to thousands of titles, but we lost something fundamental in the trade: the structural integrity of the film industry itself.

From the audience’s perspective, this looks like an unambiguous improvement. Films are easier to access, easier to resume, easier to sample. Streaming is exceptionally good at putting films in front of people quickly. But the safety net that once protected cinema was never just about ease of viewing. It was about whether discovery translated into revenue for the people who took the financial risk of making the film. Convenience alone does not sustain a production ecosystem. Money does.

We often talk about collecting physical media as a hobby — a niche for enthusiasts who like slipcovers and shelf-candy. But the decline of the physical format wasn't just a shift in consumer habit; it was a demolition of the economic foundations that once allowed cinema to absorb risk and survive failure.

Recent industry analysis — such as the British Film Institute’s economic review of UK independent cinema — finds that “the model of independent production is being shaken at its foundations” because revenues are not keeping pace with rising costs, even as digital channels grow.

The Lost Safety Net

For decades, the home video market was the silent engine of the film economy. It wasn't just a bonus revenue stream; it was the insurance policy that allowed mid-budget cinema to thrive.

As Matt Damon famously explained in his 2021 Hot Ones interview, the "long tail" revenue of physical media fundamentally changed the risk calculation for studios. A studio could greenlight a $40 million adult drama or a niche thriller, knowing that even if it underperformed at the box office, it would likely recoup its budget on the rental and sales market six months later.

This “safety net” didn’t just reduce financial risk; it changed what kinds of films could survive. It allowed movies that failed to communicate themselves in a theatrical opening to be slowly understood through repeat viewing and word of mouth.

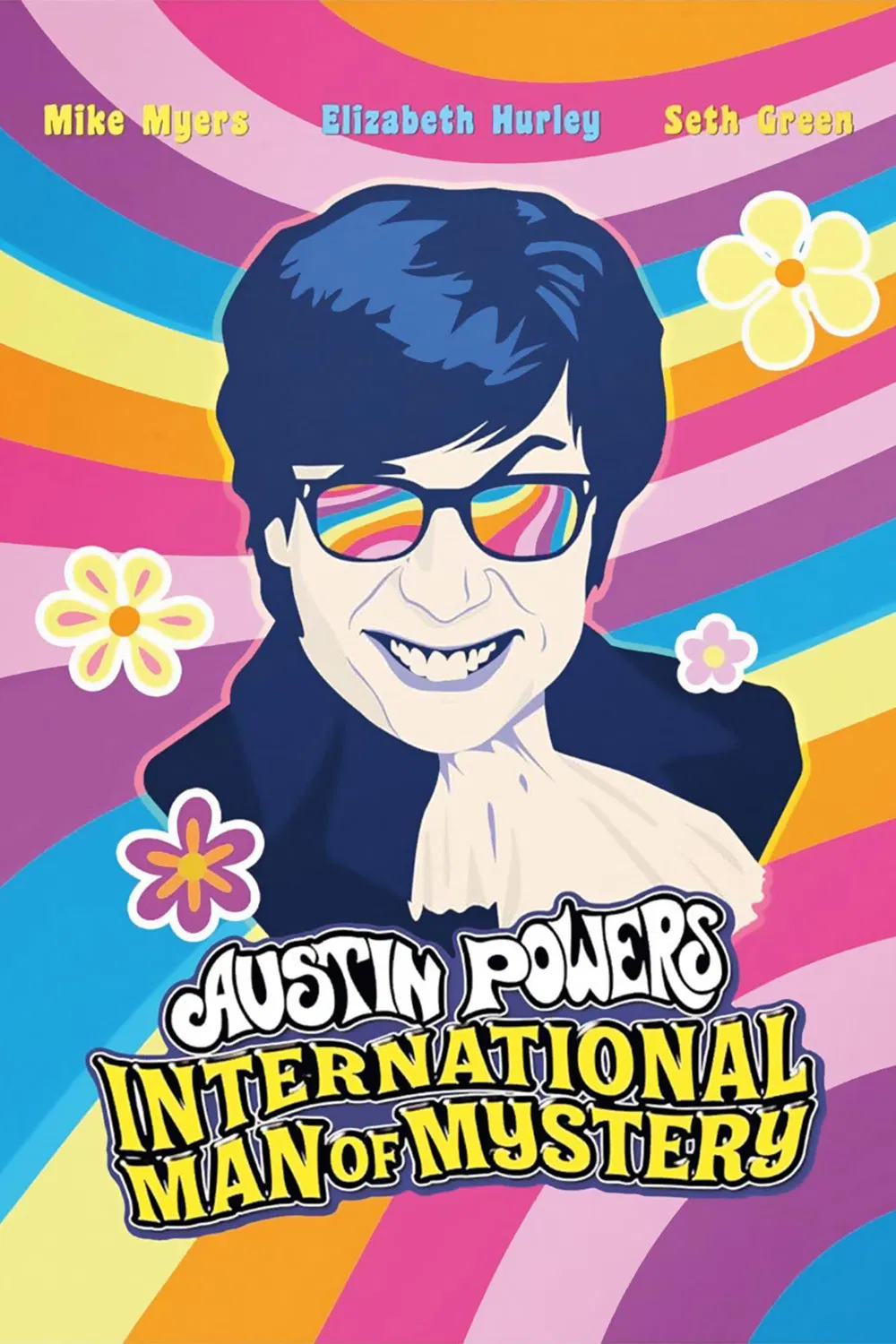

Case Study A: The Franchise That Shouldn't Exist

Austin Powers: International Man of Mystery (1997) is definitive proof of the home video multiplier. The film was a modest theatrical release, earning just $53 million domestically. In the pre-VHS era, that would have been the end of the road.

But on home video, it became a phenomenon. The "rewind factor" turned it into a cultural touchstone. Because the DVD built such a massive secondary audience, the sequel (The Spy Who Shagged Me) opened to $54.9 million in its first weekend—making more in three days than the original made in its entire theatrical run. The franchise exists solely because physical media gave the audience time to catch up.

Case Study B: The Masterpiece That Failed

John Carpenter’s The Thing (1982) is now considered one of the greatest horror films ever made. But in 1982, it was a critical and commercial disaster, grossing just $20 million against a $15 million budget.

Why? It was released just two weeks after E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial. Audiences wanted friendly, optimistic aliens, not shape-shifting body horror. Without the rental market, The Thing would have vanished into obscurity. It was the VHS tape being passed around like contraband by horror fans that allowed the film to be re-evaluated on its own terms, away from the shadow of Spielberg.

You must remember the time when it was released was the summer of E.T. And it was a very bleak and hopeless film…

— John Carpenter, interview (1996)

Case Study C: The Import Ambassador

Perhaps the most profound impact of physical media was on World Cinema. In the early 2000s, Asian cinema broke into the Western mainstream not through theaters, but through boutique DVD labels like Tartan Films.

Tartan’s "Asia Extreme" line created a unified brand for films like Oldboy (2003) and Audition (1999). Western audiences didn't just buy the movie; they trusted the label. This physical curation created a global market for directors like Park Chan-wook, paving the way for the eventual Oscar success of Parasite years later.

These examples weren’t anomalies. They were symptoms of a system designed to let films take time.

What mattered about these delayed successes was not simply that the films were re-evaluated, but that re-evaluation was monetisable. Each rediscovery could become a rental, a purchase, or a gift. Time itself generated income. Physical media transformed slow appreciation into something the industry could survive, allowing films to build audiences gradually rather than all at once.

Streaming destroyed this ecosystem. A licensing deal is a flat fee that does not scale with a film's longevity. Without the guarantee of backend revenue, studios retreated to the poles: massive franchise blockbusters (guaranteed box office) or micro-budget indies (low risk). The "middle class" of movies evaporated.

Streaming operates on a fundamentally different economic logic. A purchase is a clear, per-unit transaction; a stream is a fractional data point in a pooled system. Even when a film finds an audience over time, that attention rarely compounds into meaningful revenue unless it arrives quickly and at scale. From a filmmaker’s perspective, discovery that does not reliably convert into income is not a safety net. It is exposure.

The revenue-sharing model in streaming can be less predictable and potentially less lucrative for content creators.

The most precarious consequence of this model is what happens when a platform decides a film is no longer worth hosting. When a title is delisted, it does not merely stop earning — it becomes undiscoverable. No shelf, no catalogue, no copy circulating quietly in the background. For filmmakers, this means that even delayed interest can arrive too late to matter. Discovery without availability is indistinguishable from oblivion.

The Safety Net Now

For decades, physical media functioned as a kind of insurance policy for cinema. It did not guarantee success, nor did it reward every experiment. But it ensured that failure was not final. Films could miss their moment, find an audience slowly, and still return something to the people who made them. Time was allowed to do work — economically, not just culturally.

That system has not vanished entirely. Today, physical media survives in narrower, more specialised forms: boutique labels, limited runs, collector editions. These releases no longer underpin the industry, but they still demonstrate the same principle at a smaller scale. When audiences can buy a film outright, delayed discovery once again becomes meaningful. Attention can still turn into revenue.

What has changed is not the logic, but the reach. Physical media is no longer a default safety net; it is an exception. Most films will never receive a release substantial enough to support a long tail, and many disappear from the market once licensing windows close. In that environment, uncertainty becomes harder to tolerate, and risk narrows accordingly.

A safety net does not exist to catch every fall. It exists to make falling survivable. Physical media once played that role broadly for cinema. Today, it does so only in fragments — a reminder that the problem was never about how films are watched, but about whether they are given enough time to matter.

Film images and logos used in this article were sourced from TMDb (themoviedb.org).

Christopher Bray

Engineering open algorithms to map the invisible connections of cinema. I build discovery tools that look beyond streaming catalogs to ensure film history isn't lost to the algorithm.